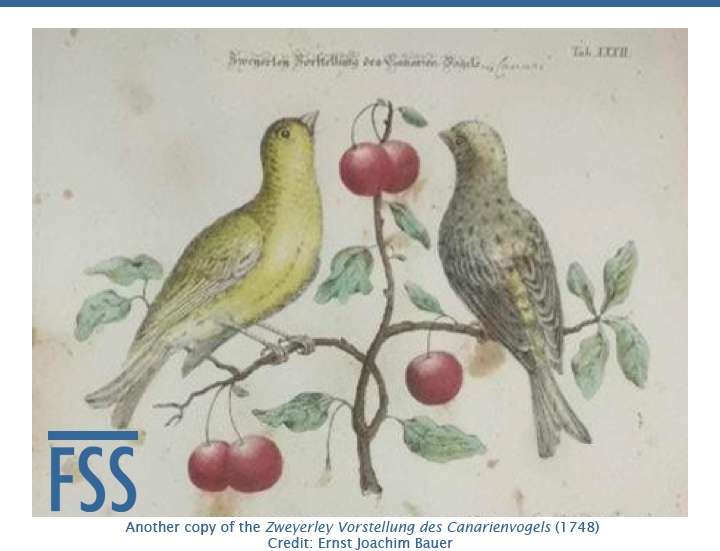

Michael Monthofer’s discovery of Johann Daniel Meye’s engraving entitled Zweyerley Vorstellung des Canarienvogels (Presentation of a pair of canary birds) is a very exciting development. After careful study Michael came to the conclusion that the bird on the right represents a canary “den man getrost als Lizard oder zumindest als sehr lizard- ähnlich bezeichnen kann” (which one can confidently call a Lizard or at least very Lizard-like). If so, it is potentially the earliest representation of the Lizard canary that has yet been discovered.

Michael was right to be cautious, but I was so intrigued by Meyer’s canaries that I have spent the last six months looking for more evidence that could confirm whether it really was a Lizard canary, or merely Lizard-like. It is an important distinction.

I can best illustrate this point by showing you another antique print which, like Meyer’s canary, portrays a bird with Lizard-like features. It might be even older. It is attributed to the studio of Nicolas Robert (1614-1685), widely accepted as the foremost botanical painter of the seventeenth century (1).

The bird on the left shares all the features of the canary portrayed by Meyer: mottling on its back, dark wings and tail, and above all, a clear cap. For all these similarities, it is not a Lizard.

Bonham’s, the auctioneers, referred to it in 2004 as a painting of the yellow canary Serinus flaviventris (now Cathigra flaviventris) but they were wrong. It is not even the yellow crowned canary Serinus flavivertex, the only African serin that often displays a short yellow cap. The clue is the orange colour on the head, which African serins do not possess. I am confident that they are a pair of saffron finches Sicalis flaveola, a South American species that may look and sing like a canary but is actually related to the tanagers.

It just goes to show that first impressions can be misleading. It is important to test the evidence, and that is what Part 2 will do.

At least we can be confident that Meyer’s print represents a pair of domestic canaries, because canary culture was highly developed in Germany in the mid eighteenth century. I had hoped that the text prepared by Georg Leonhard Huth would tell us more about Meyer’s canaries, but alas it is just a general introduction to the canary derived from previous authors. It seems the two men worked independently. Fortunately Meyer’s engraving is sufficiently detailed to offer us several clues about the identity of the birds.

The most striking feature of the bird on the right is the cap, even though its definition is rather hazy. It also possesses dark wings and tail, and its ground colour is very similar to that of a silver Lizard. Unfortunately there are no spangles, just some dark feathers scattered over the back, neck and head. The bird on the left is drawn from a different angle so that we see only its underside, a bright yellow colour.

Michael Monthofer was of the opinion that they represented the two most popular types of canaries described in London in 1779 (2):

“There are two distinct species of Canary-birds known among breeders, besides some varieties under each, which latter are not material to enter into. These are those birds which are all yellow, and those which are mottled, with a yellow crown: the former, in the breeding stile being called gay birds, and the latter fancy birds.”

Thus he identified the bird on the left as a ‘gay bird’ (meaning a clear yellow canary) and the bird on the right as a ‘fancy bird’, or in Michael’s words, a “Lizard oder zumindest als sehr lizard- ähnlich” (a Lizard or at least very Lizard-like).

My immediate reaction was to agree with him, but I began to have doubts as I looked more closely. If you examine the bird on the left you will see that the wing coverts and alula are black with a light fringe. It is a sure sign that some, if not all, of the feathers in the wing were dark, and therefore the bird cannot have been a ‘gay’ canary.

The combination of a yellow body and dark wings will, of course, raise speculation that the bird could be a London Fancy, or at least a spangle-back, but there are two good reasons why that is very unlikely. First, there is no evidence from historical texts that the London Fancy existed at that time. Second, if the bird was a London Fancy, it would surely have been drawn from above to display the dramatic contrast between the yellow body and the dark wings and tail.

Now let us turn our attention to the bird on the right. I agree that it is Lizard-like thanks to the presence of a cap, but even that is open to doubt. Of the four copies of the engraving I have seen, three show a canary with a cap (see above and another in Part 1) but the fourth does not. I had discovered that a copy of Meyer’s book was held at the National History Museum at Tring, and Hein van Grouw was kind enough to photograph plate XXXII for me. Here it is:

The explanation is straightforward: some variation is inevitable because the engravings were hand coloured, probably by more than one person. Note the arbitrary application of yellow to the left and right wings, and the absence of colour below the eye. The bird on the left has a yellow tail feather. These anomalies confirm that the Tring print had been coloured with a lack of care.

There is, however, a much more important flaw that applies to all the prints. If the bird really was a Lizard it should display continuous chains of spangles running down its back, but all we see are random dark ticks or flecks against a grey-green background. It is only on the neck that they are arranged in lines. Those dark markings were part of the original engraving, they do not vary from print to print.

Let’s remind ourselves what the spangles of the Lizard canary should look like when viewed from this angle. In good Lizards they are regular and precise.

The only canary that sometimes displays a combination of a clear cap and dark ticks on the head and body is the spangle-back, so could that be the answer? It is very unlikely. The individual flecks on a spangle-back only become apparent when the surrounding feathers have lost most of their melanin; they stand out against the yellow or buff background. Where the surrounding feathers retain their melanin, as in Meyer’s drawing, the dark feathers appear as stripes which may (or may not) be spangled.

Michael raised the possibility that the Lizard canary could have been of German origin. It is not impossible. German breeders were at the forefront of canary culture in the seventeenth century and excelled at improving features such as the song and the crest. They also exported their canaries across Europe. Could Meyer’s canary have been a primitive forerunner of the Lizard perhaps? We can be confident that the answer is ‘no’ for the simple reason that spangled canaries had been refined in England long before Meyer’s print was published.

Ward (1728) describes birds that . . .

“ . . . a few years ago were brought from France, but since much improved in the colour by our Breeders at Home; the finest sort are of a beautiful bright Yellow, bespangled with an Intermixture of jet black spots, having little or no white about them”. (3)

The objections to Meyer’s canary being a Lizard keep mounting. We can’t even blame poor draughtsmanship because we know that Meyer was capable of drawing spangle-like markings, as his engraving of Der Gegler (the brambling, Fringilla montifringilla) shows. If Meyer had seen regular spangles we can be confident he would have drawn them.

How then do we explain the canaries depicted by Meyer? How did they come to be present in Nuremberg? I will try to answer those questions in Part 3.

Footnotes:

- Robert was appointed as Peintre Ordinaire du Roi to Louis XIV, the Sun King, and became the first significant contributor to a collection of fine watercolours on vellum that became known as the Velins du Roi (the King’s Vellums). He produced five volumes during his lifetime comprising some 500 plants from the Royal Gardens and 200 birds from the aviaries at Versailles. Supplements to Robert’s works were added by his pupils, and reprints continued up to the mid eighteenth century. The date of this particular print is not given in the auction description, but the lack of a volume reference suggests it is probably a later edition.

- “A Natural History of English Song Birds”, by Eleazar Albin, London (1779). This edition, published after Albin’s death, contains additional information about canaries written by an anonymous contributor who was evidently familiar with London’s canary societies. A slightly modified description was published in 1791; the key difference being that ‘‘fancy birds’’ became “spangled or fancy birds”, confirming they were what we now call the Lizard canary.

- “The Bird-Fancier’s Recreation” by T. Ward, London (1728). For the benefit of readers whose first language is not English, ‘bespangled’ means ‘covered with spangles’.

To me Meyer’s print is not very precise but it represents a pair of european serins from the proportion of their overall measurements and the size of their wings. On the left is the cock bird bearing his colourful yellow feathering and on the right is the hen very pale and strecked.

Brehm on his “Handbuch der Naturgeschichte aller Vogel” p 255 call them Serinus Meridionalis.

Laubmann 1913 call them Serinus Canarius Germanicus.

Meyer on his “Sweijerleij Sorftellintg des Kanarien vogels” Tab XXXII published on 1748 is referring to Gesner & Linnae.

Gesner in his “Historia Animalium” Liber III mentions that the serin is very present in Germany near Munich & Francfort where they call the serin : girlitz and near Tridentum : hirngrillen.

Many differents words for the same bird.